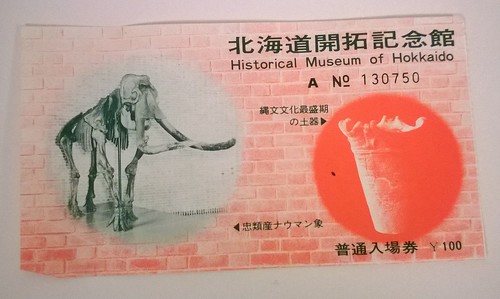

In the entrance hall of the Historical Museum of Hokkaido stand two enormous skeletons — a mammoth and a Naumann’s elephant, another type of woolly, Pleistocene proboscidean native to Japan. By the time I visited the museum at age three or four, I had seen living elephants at the Ueno Zoo in Tokyo and the Maruyama Zoo in Sapporo. The enormous curved tusks arched over my head, and I knew instantly that I was in the presence of something altogether different and wonderful.

We walked past cases of Jomon pottery and through the dark halls of ethnographic dioramas depicting Ainu lifeways. The museum opened just a few years earlier, in 1971, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Western-style colonization of Hokkaido by ethnic Japanese people following the Meiji Restoration. Hokkaido today is full of beautiful Victorian buildings that would be at home in any of the nicer neighborhoods of San Francisco, Chicago, or Seattle. As is typical the world over, the process of colonization did not go well for the aboriginal peoples. But I’ll save a discussion of the complexities of modern Japan as a multiethnic society for another day…

I got scared of the strange, dimly lit mannequins with their beards and furs, so my mother took me outside to walk around on the museum grounds, where we encountered a rock wall of hand stencils like the ones I’d see when I grew older, a motif that ties together Paleolithic cultures the world over.

Despite my fear, from that moment on, I became fascinated with humanity’s shared past. I needed to understand those other people who lived in a time when mammoths and aurochs roamed the open steppe. By the time I was 5 had learned that people who studied deep human history were called archaeologists, and the people who dug up mammoths were called paleontologists. As awed as I was by that mammoth, it was the people who intrigued me. Following the invariable fireman phase and a brief flirtation with wanting to be a ballerina (after seeing the Bolshoi Ballet perform Swan Lake), I knew I wanted to become an archaeologist.

When adults asked me, I would inform them of this fact, to which most would say, “So you want to dig up dinosaurs? That sounds like fun!”

“No,” I would reply, “That’s a paleontologist, like Louis Leakey in Africa. I want to become an archaeologist.”

By the mid-80’s, adults would then follow with “Oh, of course, like Indiana Jones!”

I’d sigh and say, “No, not like him. Indiana Jones is just a grave robber. I want to be like Heinrich Schliemann. He discovered Troy.”

Large proportions of my education having consisted of back issues of National Geographic and old sets of Encyclopædia Britannica, I was, in hindsight, rather insufferable.

There really are moments in the course of your life when it shifts to a new direction. In the years since, I’ve collected Jomon potsherds from carrot fields in Yokohama, participated in digs (the Tategahana Paleolithic site at Lake Nojiri and Tall al-`Umayri in Jordan), held Neanderthal tools in my hand, and pondered axial precession under Newgrange.

And yet, nothing will ever compare to my first sight of a mammoth skeleton that day back in Hokkaido. Some day, perhaps I’ll see one in the flesh…