As a child of ex-pat parents who moved all over Japan before we moved “home” to the States when I was a teenager, there are few places on Earth I feel I’ve put down roots in the way those who were born and grew up in the same city, state, or even country feel they do. Oddly perhaps, this has given me the freedom to lay claim to whatever place I feel a deep connection to, from the darkened roads of Tillamook to Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey; from the inner chamber of Newgrange to the aircraft carrier USS Midway.

My feelings about family and cultural heritage are as convoluted as my sense of home. It might come as no surprise that my primary comfort food is cold soba noodles with fishy dipping sauce green with wasabi, but I also feel a warm glow of connectedness when I pick up a morsel of mesir wat with my shred of injera. After all, aren’t we all Ethiopian?

Nevertheless, I’ve felt an increasing compulsion to connect with my more recent family heritage over the last couple of years (resulting in exploration of my Loyalist Canadian lineage, for example). Living in Seattle today, I’m most interested in the stories of the first Becraft families who arrived here in the late 19th century.

Family photos show great-great-grandfather James Samuel Becraft with his logging crew in Skagit and Island Counties north of Seattle, but oral family history only seems to begin when James Samuel joined the Seventh-day Adventist church, and everything about the rest of his family and their ancestors remains a mystery.

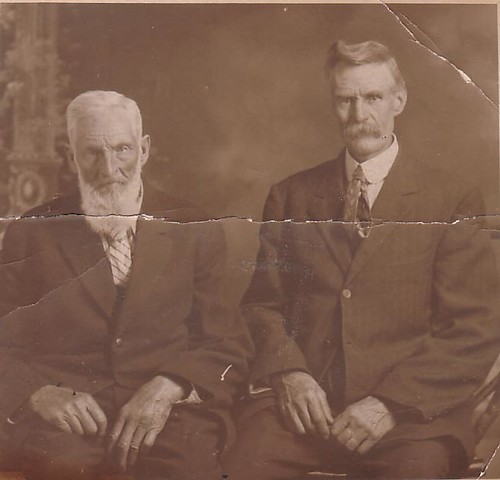

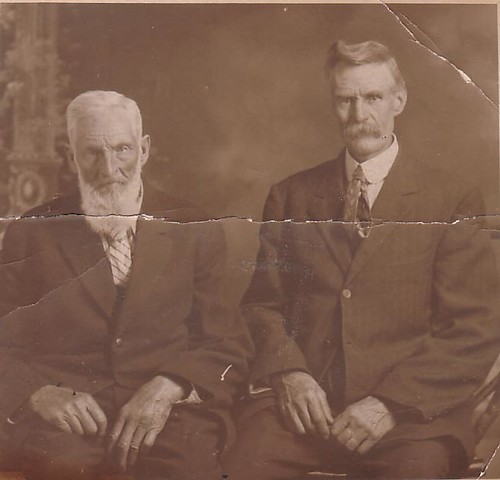

This next photo shows James S. Becraft with his father, James Thomas Becraft, about whom I knew very little until doing a bit of research.

As it turns out, James Thomas Becraft (born in 1827 in Booneville, Kentucky) traveled overland to Plumas County, California in 1853 with his wife Rebecca. He worked alternately as a gold miner and logger until 1873, when he became a farmer. Rebecca died in 1878, and by 1900, James T. had moved north to Oregon, then on to Sedro-Woolley, Washington by 1910 to live with his son Charles Edward, until James T. died the next year.

My wife and I visit friends in Sedro-Woolley fairly regularly, so I did a bit more research before a trip up there last week and confirmed that James T. Becraft was indeed buried in Sedro-Woolley. My friend Josh is a bit of a historian himself, so he and I drove to the Union Cemetery in Sedro-Woolley this past Saturday and scoured alternate rows for my relatives. There are seventeen Becrafts buried in Sedro-Woolley, and we had found nearly all of them — but not my direct ancestor James Thomas — when we called it a day and drove off.

As Josh sped up, I noticed what looked like a map on a sign by the side of the road, and I called “Wait!” He turned the car around and we began looking through the section of the cemetery we hadn’t noticed before, where Oddfellows were buried. Within a few minutes, we had found Great-Great-Great-Grandpa Becraft.

There’s a sense of place that emerges from the overwhelming cultural significance of the archaic structure one stands within — Newgrange or Westminster Abbey — and the sense of connectedness that place brings you as a member of the broader human species. But to stand before the grave of my forefather is another sense of place entirely and a very different kind of connectedness.

To the list of places where my roots spread beneath the ground, I now add Sedro-Woolley, one of my many homes.