-

Paleolithic archaeology, software design, and the social brain

Over the past 18 months, I’ve immersed myself deeper and deeper in the Paleolithic, reading scores of books and journal articles. Why?

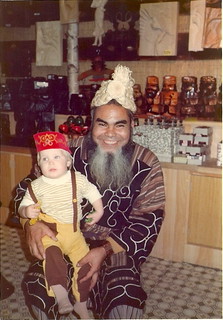

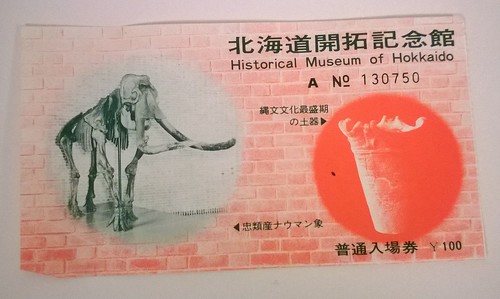

Ever since my first visit at about age four to the Historical Museum of Hokkaido, with its mammoth skeletons and Paleolithic dioramas, I’ve been fascinating by the archaeology of deep human history (as Clive Gamble puts it in the subtitle of his exceptional book Settling the Earth). I wandered by chance onto the Tategahana Paleolithic Site at Lake Nojiri in Nagano during an excavation, walked carrot fields in Yokohama looking for Jomon potsherds, and when I traveled to Jordan during college for an Iron Age dig, I spent my evenings surface-collecting Middle Paleolithic tools from a nearby barley field. The vast, mostly unknown and seemingly unrelatable world of the Stone Age seems so much more interesting than the thoroughly modern world of Archimedes, Hadrian, and Augustine of Hippo.

(more…) -

Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition reading list

The period of the Paleolithic that fascinates me most, as I know it does many archaeologists, is the transition between the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Paleolithic. I’m particularly fascinated by archaeological work in parts of the world where anatomically modern humans (AMH) and Neanderthals met, potentially interacted, and certainly interbred. The two most likely areas where this happened, based on archaeogenetic and archaeological evidence, are the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Europe.

While the genetics are at this point incontrovertible — all non-African modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA, and recent research has proved that gene flow also occurred in the other direction — what intrigues me most are the cultural markers of interaction between AMH and Neanderthals. Similarly, what constitutes behavioral rather than merely anatomical modernity? Thus, the Mode 3 technologies associated with AMH at several sites in the Levant and Mode 4 technologies (and potentially symbolic behavior such as personal adornment) associated with Neanderthals at Châtelperronian sites like Saint-Cesaire and Les Cottés in France represent amazing opportunities to answer these questions.

- The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe

by Clive Gamble (1986)

- The Human Revolution: Behavioural and Biological Perspectives on the Origins of Modern Humans

edited by Paul Mellars & Chris Stringer (1989)

- Context of a Late Neandertal: Implications of Multidisciplinary Research for the Transistion to Upper Paleolithic Adaptations at Saint-Cesaire, Charente-Maritime, France

Ed. by François Lévêque, et al (1993)

- Rethinking the Human Revolution

edited by Paul Mellars, Katie Boyle, Ofer Bar-Yosef, & Chris Stringer (2007)

- Settling the Earth: The Archaeology of Deep Human History

by Clive Gamble (2013)

- Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide

by John J. Shea (2013)

- Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes

by Svante Pääbo (2014)

- The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction

by Pat Shipman (2015)

- The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe

-

The Shape of Content to Come

Or, Information Architecture, Minimalist music, LEGO bricks, and a visit from the President of the People’s Republic of China

As I sat stuck on the bus yesterday for an hour and a half, crawling through traffic delayed and re-routed by an impending visit from President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China, I listened for the first time to John Adams’ 1987 opera Nixon in China.

I grew up listening both to the masters of “traditional” classical music and to revolutionary 20th-century composers like Copeland and Stravinsky — the first CD I ever bought for myself, back in 1983 (the year CDs were released in Japan), was the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra’s recording of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Later, I learned to love opera when I sang in the chorus for Carmen with the oldest active symphony west of the Mississippi (a fun fact about the Walla Walla Symphony). But despite passionate recommendations from Music Major friends in college, I’d never really dug particularly deeply into Philip Glass, Arvo Pärt, Terry Riley, or John Adams. Hearing The Chairman Dances on the radio over the weekend, I realized I’d been missing something.

Whether writing software documentation earlier in my career as a technical writer, specifications and user stories more recently as a product manager, or poetry and fiction whenever I can find the creative and emotional space to write it, music has always played a significant part in my writing process. From Bach and Beethoven to Johnny Cash and Sigur Rós, just about any music helps me focus and concentrate, while the right music can help me maintain the emotional state I want to explore when writing poetry in particular.

(more…) -

Upper Paleolithic reading list

When most of us think about the Paleolithic, if we think about it at all, we think of our “Stone Age” ancestors clad in fur against the Ice Age cold, leaving their brightly painted caves to hunt mammoth. As a teenager in 1989, I visited the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian and bought one of my first books specifically about the Paleolithic in the gift shop, Paul Bahn and Jean Vertut’s gorgeous Images of the Ice Age. Through no fault of the authors, the book reinforced my childhood view of “deep” human history being a time populated by mammoths and men — humans like us.

As true as it may feel, the Upper Paleolithic is hardly ancient in the grand scheme of things, representing as little as one quarter of our species’ existence, and a minuscule fraction of the time our genus Homo has walked the earth. Nevertheless, the Upper Paleolithic, as remote as it may seem to all of us living in the post-Neolithic Holocene, still somehow feels like “our” Stone Age — a time we can relate to, with its art, complex technology, and nearly global scale.

Quibbles with perceptions of antiquity aside, it’s hard to argue that the Upper Paleolithic wasn’t beautiful. The books in my Upper Paleolithic reading list reflect the beauty and complexity of the time when we finally became us.

- Images of the Ice Age

by Paul G. Bahn & Jean Vertut (1988)

- The Cave Beneath the Sea: Paleolithic Images at Cosquer

by Jean Clottes & Jean Courtin (1994)

- Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave (The Oldest Known Paintings in the World)

by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps, Christian Hillaire, with an introduction by Paul Bahn and epilogue by Jean Clottes (1995)

- Kebara Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel, Part I: The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archaeology

edited by Ofer Bar-Yosef & Liliane Meignen (2008)

- Cave Art

by Jean Clottes (2010)

- Images of the Ice Age

-

A Paleolithic typology joke

François Bordes on how to tell the difference between a Mousterian point and a convergent scraper:

Grizzly by “Life as Art” on Flickr The best way to decide is to haft the piece and try to kill a bear with it. If the result is successful, then it is a point; if not, then it should be considered a convergent scraper. One of the problems with this approach is that it can quickly exhaust the available supply of bears or typologists

– As paraphrased by André Debénath and Harold L. Dibble in Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe(1994)

-

The detritus of hominid existence

Debénath & Dibble on the sheer scale of what lies beneath:

Imagine … that during the time of the Acheulian in Europe, which lasted for at least 500,000 years, there was a constant population of 5,000 active tool makers. Imagine also that each of these flintknappers made only ten bifaces per year and perhaps 100 flake tools. Even with such conservative parameters…, this would have resulted in the production of 25,000,000,000 bifaces and 250,000,000,000 flake tools, of which only a minuscule proportion has been collected during the history of Paleolithic research.

– André Debénath and Harold L. Dibble in Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe(1994)

-

Sherding for Jomon pottery in Yokohama

In 1983, my family moved from the medieval castle town of Himeji in western Japan to the outskirts of Yokohama. We had also lived in Yokohama for two years after I was born in Tokyo, and my minister father was being transferred back to work at his church’s headquarters in Asahi-ku. We lived in a mouldering compound of American ranch houses built for western missionaries. Constructed 40 years earlier in an era when American missionaries had Japanese maids, the houses even had a small apartment on the other side of the kitchen, behind the garage — a single tiny room with tatami mats and a bathroom with a deep Japanese furo that I sometimes preferred to the American bathtubs elsewhere in the house.

Through the power of satellite photography, I can see my old home, the easternmost house in the row of four toward the center of this screen capture (sent to me by a friend in 2011).

The first thing I learned in Yokohama was to drop my Kansai accent and start talking like the Kanto children around me.

One of the next things I was taught was that we lived atop a giant Jōmon midden. A midden is the kitchen scrap-heap of an archaeological site. Like the famous Tells of Middle Eastern archaeology, kitchen middens can grow to enormous proportions over the millennia as humans live near or on top of their growing garbage heap. Shell middens specifically include shellfish remains, but in Japan the term 貝塚 (kaizuka) is used as a general term for various types of archaeological middens, regardless of any evidence of actual shellfish processing at the site. Since the 1980s, archaeologists have clarified that our neighborhood sat on an upland terrace overlooking the Onda River valley — part of the larger Nagatsuta–Wakabadai Jōmon settlement complex, where overlapping habitation layers and midden deposits have surfaced for decades.

The Jōmon period (縄文時代) began about 16,000 years ago and lasted until the beginning of the Yayoi period (弥生時代) in about 300 BCE, with the introduction of rice-based agriculture. The Jōmon people made some of the earliest pottery in the world, but despite their sedentary lifestyle in villages and their intensive use of earthenware (土器), they were a predominantly pre-agricultural society of hunter-gatherers. Thus, the Jōmon period is considered transitional between the Paleolithic in Japan (旧石器時代) and the Iron Age Yayoi with their bronze bells, iron swords, and rice paddies.

Rather than a sudden leap from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age, the transition to the Yayoi period reflects a long process of interaction. Immigrant farming communities from the continent brought wet-rice agriculture and metal tools to regions already inhabited by Jōmon descendants, producing centuries of overlap and exchange.

Starting around 2,300 years ago, the Yayoi culture and the later Yamato culture steadily replaced the Jōmon culture. The Ainu people of Hokkaido preserve the highest proportion of Jōmon ancestry today, though genetic traces of these ancient islanders persist across all modern Japanese populations. With the colonization of Hokkaido following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the invasion of the Yamato people across the islands of the Japanese archipelago was finally complete after more than two thousand years.

As I learned myself while attending Japanese elementary school in Yokohama, every Japanese child learns key archaeological details about the Jōmon period. Crafted without a wheel using coiled clay and fired in an open bonfire at fairly low temperatures, Jōmon potters often applied designs to their earthenware by pressing or rolling twine onto the wet clay. This is where the archaeological period gets its name: “Jōmon” means “rope-marked”.

Archaeological sites are so common in the densely populated country that some go unexcavated. Near my home in Yokohama, modern machines with their ever-deeper plowing turned up more and more Jōmon potsherds in each furrow. Nearly every weekend for three years, I scoured the fields for these potsherds, hauling home plastic shopping bags full of broken pieces pressed with the classic, rope-marked pattern of pottery from the Early Jōmon phase (roughly 4,500–3,500 BCE).

A few years after we moved away from Yokohama, on a day when I must have felt particularly bored or lonely, I went through one of my boxes of sherds and managed to assemble a larger section from 6 different pieces. The hours I spent trying to fit potsherds together indicate just how seriously I took my future as an archaeologist.

Every so often in Yokohama, I would find a more substantial potsherd, usually from a thicker vessel with the kinds of beautifully embossed patterns more typical of the Middle and Late Jōmon phases. Given their beauty, these were rare and exciting finds, even if the farmers didn’t seem to think so — they were usually tossed to the edge of the field like troublesome stones.

The vast carrot fields atop the hill to the north of our little American neighborhood yielded the most pottery — from small fragments to large sherds with ornate, swirling patterns.

In the years since a former neighbor emailed me a screenshot of our old houses on Google Maps, a new imaging pass has revealed that our four American-style oddities have been torn down, replaced by a modern neighborhood of over thirty proper Japanese houses. Similarly, the carrot fields to the north of the missionary compound have been replaced by the Wakabadai apartment complex — a convenient, one-hour train ride straight into downtown Tokyo.

I can take a virtual walk along the Tomei Expressway to my old elementary school, and I can even see the shadow of the Japanese lantern where I had my picture taken when I was a baby. As I peruse photos taken from space of the Japanese streets I knew so well, while connected from my living room in Seattle to a global network of computers, it becomes clear how much has changed in just 30 years. Our satellites also look outward, finding unseen planets and revealing a universe of limitless wonder.

Yet, as I hold a 5,000-year-old Jōmon potsherd in my hand, I wonder what we’ve lost beneath all those apartment buildings, the bank, the ramen shop, and the train station with its express service to Shinjuku. What do we destroy when we pave over ten thousand years of history for another hamburger joint? But even as urban growth erased the visible traces, rescue archaeologists were racing ahead of the bulldozers, documenting sites just like ours — a reminder that every lost field may still whisper its story through the fragments we kept.

How will future archaeologists assess these first layers as they scrape away our present and reveal the past we share with them?

-

Of mammoths past and mammoths future

In the entrance hall of the Historical Museum of Hokkaido stand two enormous skeletons — a mammoth and a Naumann’s elephant, another type of woolly, Pleistocene proboscidean native to Japan. By the time I visited the museum at age three or four, I had seen living elephants at the Ueno Zoo in Tokyo and the Maruyama Zoo in Sapporo. The enormous curved tusks arched over my head, and I knew instantly that I was in the presence of something altogether different and wonderful.

We walked past cases of Jomon pottery and through the dark halls of ethnographic dioramas depicting Ainu lifeways. The museum opened just a few years earlier, in 1971, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Western-style colonization of Hokkaido by ethnic Japanese people following the Meiji Restoration. Hokkaido today is full of beautiful Victorian buildings that would be at home in any of the nicer neighborhoods of San Francisco, Chicago, or Seattle. As is typical the world over, the process of colonization did not go well for the aboriginal peoples. But I’ll save a discussion of the complexities of modern Japan as a multiethnic society for another day…

I got scared of the strange, dimly lit mannequins with their beards and furs, so my mother took me outside to walk around on the museum grounds, where we encountered a rock wall of hand stencils like the ones I’d see when I grew older, a motif that ties together Paleolithic cultures the world over.

Despite my fear, from that moment on, I became fascinated with humanity’s shared past. I needed to understand those other people who lived in a time when mammoths and aurochs roamed the open steppe. By the time I was 5 had learned that people who studied deep human history were called archaeologists, and the people who dug up mammoths were called paleontologists. As awed as I was by that mammoth, it was the people who intrigued me. Following the invariable fireman phase and a brief flirtation with wanting to be a ballerina (after seeing the Bolshoi Ballet perform Swan Lake), I knew I wanted to become an archaeologist.

When adults asked me, I would inform them of this fact, to which most would say, “So you want to dig up dinosaurs? That sounds like fun!”

“No,” I would reply, “That’s a paleontologist, like Louis Leakey in Africa. I want to become an archaeologist.”

By the mid-80’s, adults would then follow with “Oh, of course, like Indiana Jones!”

I’d sigh and say, “No, not like him. Indiana Jones is just a grave robber. I want to be like Heinrich Schliemann. He discovered Troy.”

Large proportions of my education having consisted of back issues of National Geographic and old sets of Encyclopædia Britannica, I was, in hindsight, rather insufferable.

There really are moments in the course of your life when it shifts to a new direction. In the years since, I’ve collected Jomon potsherds from carrot fields in Yokohama, participated in digs (the Tategahana Paleolithic site at Lake Nojiri and Tall al-`Umayri in Jordan), held Neanderthal tools in my hand, and pondered axial precession under Newgrange.

And yet, nothing will ever compare to my first sight of a mammoth skeleton that day back in Hokkaido. Some day, perhaps I’ll see one in the flesh…

-

Middle Paleolithic reading list

I’ve begun narrowing my reading down from works about the Paleolithic as a whole to the Middle Paleolithic in particular.

While it’s been fascinating to see perspectives on Neanderthals evolve in popular non-fiction over the last 30 years, immersing myself in stratigraphy, typology, palynology, faunal assemblages, taphonomy, and (most exciting!) spatial organization has proved deeply rewarding. To that end, my reading has incorporated more and more site reports by the likes of Bordes (Combe Grenal and Peche de l’Aze); Lévêque, et al (Saint-Cesaire); Bar-Yosef, et al (Kebara); and Akazawa & Muhesan (Dederiya).

- A Tale of Two Caves

by François Bordes (1972)

- Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe

by André Debénath & Harold L. Dibble (1994)

- The Neanderthal Legacy: An Archaeological Perspective from Western Europe

by Paul Mellars (1995)

- Neanderthal Burials: Excavations of the Dederiya Cave: Afrin, Syria

edited by Takeru Akazawa & Sultan Muhesan (2003)

- The Middle Paleolithic: Adaptation, Behavior, and Variability

edited by Harold Dibble & Paul Mellars (2003)

- A Tale of Two Caves

-

General Paleolithic reading list

With my lithic technology reading list nearly out of the way, I continue to (pardon the pun) go deep on the Paleolithic. I’m particularly fascinated by the Middle Paleolithic, dominated in Europe by the Mousterian lithic industry created by our Neanderthal cousins.

Nevertheless, my Paleolithic reading list remains fairly diverse.

- Manual of the Antiquity of Man by J.P. Maclean (1878)

- Disclosing the Past

by Mary Leakey (1984)

- Encyclopedia of Human Evolution and Prehistory

edited by Eric Delson, Ian Tattersall, John A. Van Couvering, and Alison S. Brooks (2000)

- The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe

by Barry Cunliffe (2001)

- Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins (MacSci)

by Ian Tattersall (2013)

- Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth

by Chris Stringer (2013)

- Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story

by Rob Dinnis and Chris Stringer (2014)

I’m especially enjoying the first book in my list, a copy from 1878 that I spotted by chance and picked up for $4.00 at a used bookstore 25 years ago in Union Springs, NY. It’s a fascinating view into the state of paleoanthropology in the era when Darwin, Lyell, and Huxley were all still alive.

More paleolithic archaeology and paleoanthropology reading lists:

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.